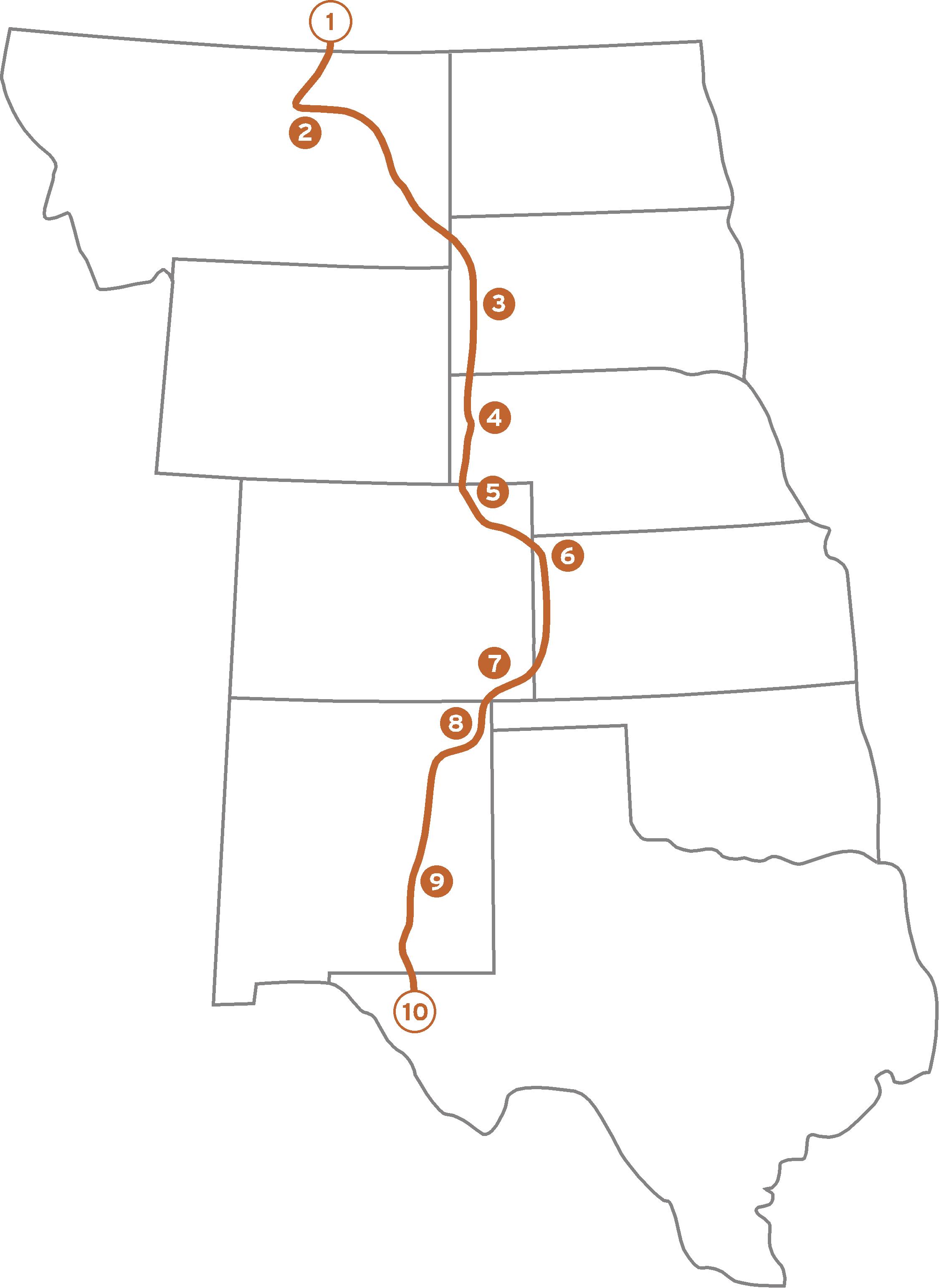

The next few entries will take a look at the various rivers that cross the Great Plains. From the Missouri in Montana to the Pecos in New Mexico, many great rivers flow across the region. They are scenic, historic, big, and attract a wide variety of wildlife. There are also countless smaller tributaries that wind their way from west to east across the prairies, but let’s take a look at some of the big ones.

The next few entries will take a look at the various rivers that cross the Great Plains. From the Missouri in Montana to the Pecos in New Mexico, many great rivers flow across the region. They are scenic, historic, big, and attract a wide variety of wildlife. There are also countless smaller tributaries that wind their way from west to east across the prairies, but let’s take a look at some of the big ones.

Rivers in the Great Plains generally flow from west to east. The highest elevations are in the west and the lowest elevations are in the east, and last I checked, water flows downhill. That said, the first river we encounter as we head south from the Canadian border is the Missouri River. The Missouri River, a.k.a. “The Big Muddy” is the longest river in North America and runs from the Rocky Mountains in Montana to where it joins the Mississippi River in Missouri. It drains an area more than twice the size of Texas which includes all or part of nine states as well as parts of two Canadian provinces. The average flow is about 90,000 cubic feet per second. That’s about 720,000 gallons per second! At this rate, the river could fill Lake Erie in just nine months.

People have been in the region for at least 10,000 years, and many cultures rose near the river culminating in the horse culture tribes of the plains such as the Sioux, the Hidatsa, and the Crow. The first Europeans to have a look at the Big Muddy were Frenchmen Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette. They saw the river in late spring of 1673 when it was at an impressive flood stage. Jolliet writes: “I never saw anything more terrific.”

The most famous pair to ever battle the relentless forces of the river were undoubtedly Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Their journey up the Missouri in 1804 has become one of the defining adventures in the history of the United States. Though their arrival and charting of the American West spelled the beginning of the end for the native cultures that still existed, it remains a great story, and launched the modern history of the West.

Today, the Missouri is highly regulated and controlled for most of its length by various dams and hydrological engineering projects. These projects are designed to control floods, store water, and in some cases, provide electricity. Those are the benefits. The downside is the loss of the wildness and the beauty of the river. As with an animal in a circus, one feels a sense of pity when looking at such a tamed beast. We need electricity, and we need water in the arid West, but we also must acknowledge what we have lost in the process. The Missouri is a river no more.

2 Responses

Fascinating stuff – you know I always thought of the Missouri as a river of “The South” and never realised it’s source was as far north as Montana!

Strange how rivers often get named for the states in which they end as opposed to the states in which they begin. The Mississippi is another example as it begins in Minnesota.